Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

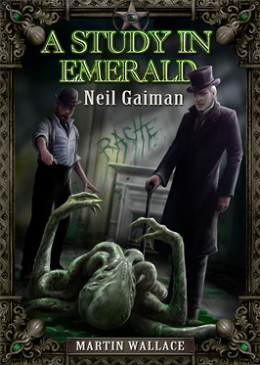

Today we’re looking at Neil Gaiman’s “A Study in Emerald,” first published in 2003 in Shadows Over Baker Street (edited by Michael Reeves and John Pelan). Spoilers ahead. We’re not worthy, we’re not worthy.

“She was called Victoria, because she had beaten us in battle, seven hundred years before, and she was called Gloriana, because she was glorious, and she was called the Queen, because the human mouth was not shaped to say her true name. She was huge, huger than I had imagined possible, and she squatted in the shadows staring down at us, without moving.”

Summary

Narrator, a retired army major, returns to Albion from Afghanistan, where gods and men are savages unwilling to be ruled by London, Berlin, or Moscow. The Afghan cave-folk tortured Major by offering him to a leech-mouthed thing in an underground lake; the encounter withered his shoulder and shredded his nerves. Once a fearless marksman, he now screams at night. Evicted from his London lodgings, he’s introduced to a possible roommate in the laboratories at St. Bart’s. This fellow, whom Major soon calls “my friend,” quickly deduces his background. He won’t mind screaming if Major won’t mind Friend’s irregular hours, his use of the sitting room for target practice and meeting clients, or the fact that he’s selfish, private, and easily bored.

The two take rooms in Baker Street. Major wonders at the miscellany of Friend’s clients and his uncanny deductive powers. One morning Inspector Lestrade visits. Major sits in on their meeting and learns that Friend is London’s only consulting detective, aiding more traditional investigators who find themselves baffled. He accompanies Friend to a murder scene. Friend has a feeling they’ve fought the good fight together in the past or future, and he trusts Major as he trusts himself.

The victim lies in a cheap bedsit, sliced open, his green blood sprayed everywhere like a gruesome study in emerald. Someone’s used this ichor to write on the wall: RACHE. Lestrade figures that’s a truncated RACHEL, so better look for a woman. Friend disagrees. He’s already noted, of course, that the victim’s of the blood royal—come on, the ichor, the number of limbs, the eyes? Lestrade admits the corpse was Prince Franz Drago of Bohemia, her Majesty Victoria’s nephew. Friend suggests RACHE might be “Revenge” in German, or it might have another meaning—look it up. Friend collects ash from beside the fireplace, and the two leave. Major’s shaken—he’s never seen a Royal before. Well, he’ll soon see a live one, for a Palace carriage awaits them, and some invitations can’t be rejected.

At the Palace, they meet Prince Albert (human), and then the Queen. Seven hundred years ago, she conquered Albion (hence Victoria—the human mouth can’t speak her real name.) Huge, many-limbed, squatting in shadow, she speaks telepathically to Friend. She tells Major he’s to be Friend’s worthy companion. She touches his wounded shoulder, causing first profound pain, then a sense of well-being. This crime must be solved, the Queen says.

At home, Major sees that his frog-white scar is turning pink, healing.

Friend assumes many disguises as he pursues the case. At last he invites Major to accompany him to the theater. The play impresses Major. In “The Great Old Ones Come,” people in a seaside village observe creatures rising from the water. A priest of the Roman God claims the distant shapes are demons and must be destroyed. The hero kills him and all welcome the Old Ones, shadows cast across the stage by magic lantern: Victoria, the Black One of Egypt, the Ancient Goat and Parent of a Thousand who’s emperor of China, the Czar Unanswerable of Russia, He Who Presides over the New World, the White Lady of the Antarctic Fastness, others.

Afterwards Friend goes backstage, impersonating theatrical promoter Henry Camberley. He meets the lead actor, Vernet, and offers him a New World tour. They smoke pipes on it, with Vernet supplying his own black shag as Camberley’s forgotten his tobacco. Vernet says he can’t name the play’s author, a professional man. Camberley asks that this author expand the play, telling how the dominion of the Old Ones has saved humanity from barbarism and darkness. Vernet agrees to sign contracts at Baker Street the next day.

Friend hushes Major’s questions until they’re alone in a cab. He believes Vernet’s the “Tall Man” whose footprints he observed at the murder site, and who left shag ash by its fireplace. The professional author must be “Limping Doctor,” Prince Franz’s executioner—limping as deduced from his footprints, doctor by the neatness of his technique.

After the cab lets them out at Baker Street, the cabby ignores another hailer. Odd, says Friend. The end of his shift, says Major.

Lestrade joins our heroes to await the putative murderers. Instead they receive a note. The writer won’t address Friend as Camberley—he knows Friend’s real name, having corresponded with him about his monograph on the Dynamics of an Asteroid. Friend’s too-new pipe and ignorance of theatrical customs betrayed that he was no shag-smoking promoter. And he shouldn’t have talked freely in that cab he took home.

Writer admits to killing Prince Franz, a half-blood creature. He lured him with promises of a kidnapped convent girl, who in her innocence would go immediately insane at the sight of the prince; Franz would then have the Old One-ish delight of sucking her madness like the ripe flesh from a peach. Writer and his doctor friend are Restorationists. They want to drive off man’s Old One rulers, the ultimate act of sedition! Sating monsters like Franz is too great a price to pay for peace and prosperity.

The murderers will now disappear; don’t bother looking for them. The note’s signed RACHE, an antique term for “hunting dog.”

Lestrade initiates a manhunt, but Friend opines the murderers will lay low, then resume their business. It’s what Friend would do in their place. He’s proven right—though police tentatively identify Doctor as John or James Watson, former military surgeon, the pair aren’t found.

Major consigns his story to a strongbox until all concerned are dead. That day may come soon, given recent events in Russia. He signs off as S____ M____ Major (Retired).

What’s Cyclopean: Nothing, every word in this story is perfect.

The Degenerate Dutch: Even seven hundred years after the Old Ones turn the moon blood-red, England exists in noticeable form. In British fantasy, England tends to be as essential a component of the universe as hydrogen.

Mythos Making: The returned Old Ones include Nyarlathotep, Shub-Niggurath, and Cthulhu, as well as several less immediately identifiable entities.

Libronomicon: Oddly for a Gaiman story, books don’t play any notable part in “Study.” There’s a theatrical script, though.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Those of the blood royal feed on madness for their pleasure. It is not the price we pay for peace and prosperity. It is too high for that.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Like one of Lovecraft’s unnamed narrators, I react to this story instinctively and viscerally. Like a Holmesian detective, I can lay out clear and reasoned arguments for its quality. And as in “A Study in Emerald,” these two modes of analysis dovetail perfectly: I adore the story without reservation. It’s my favorite Lovecraftian tale, the perfect distillation of Mythosian mood.

“Emerald” was written for the 2003 Shadows Over Baker Street anthology. The appeal of the Holmes/Mythos theme was obvious; the implementation turned out to be challenging. In theory, mystery and horror should be compatible, since mystery is all about the plot and horror is all about invoking emotion. But Holmes is something else. Though ostensibly realist, Doyle’s stories make just as many assumptions about the nature of the universe as Lovecraft’s do, and the two are diametrically opposed. Sherlock Holmes lives in a world that is ultimately knowable—an alternative universe, in fact, far more knowable than the one in which we find ourselves. It has no place for butterfly-induced hurricanes, let alone R’lyeh. Phrenology works, ashes point directly to favored cigarette brands, and professions leave unmistakable marks on skin and posture.

Most of the Shadows Over Baker Street contributors chose to resolve this impossible conflict, answering the eternal question “Who’d win?” Either Holmes goes mad when deduction leads to unnameable horror, or Cthulhu cultists prove just as tractable as anyone else in the face of proper forensic methodology. Gaiman takes a different tack. In a world where the Great Old Ones not only exist, but triumph, the Great Detective is not himself at all. Instead, our heroes prove to be Doyle’s villains: the wickedly rational Moriarty and his second Moran. Moriarty is Holmes’s perfect foil, perfect enough to fool the reader right up until the end. (Or, for those up on their Holmes trivia, until the name Vernet is mentioned.)

The pitch perfect Holmes pastiche gets at everything I love about those stories. There’s the comforting rhythm of the perfect deduction, starting with M.’s analysis of his roommate-to-be, neatly paralleling the analysis of Watson in “A Study in Scarlet.” (Most housemates would get along better if they started with Holmes-style confessions of their most irritating quirks.) There’s the uncomfortable, but symbiotic, relationship between the consulting detective and the authorities. There’s the central, scribal friendship between a man who loves to show off and a man who loves to be shown off to.

The Lovecraft pastiche is both more overt and subtler. This is the sort of Holmes tale Doyle might tell, in style and content, but it’s not at all the sort of Mythos tale that Lovecraft would. The story begins long after the worst terrors embedded in the Mythos have come true—and become commonplace. The cultists have taken over, answering to their unholy overlords. Royalty exudes both fear and fascination, and leaders who give prosperity with one hand (limb) can carry out dreadful deeds behind closed doors. The world isn’t entirely like ours, though; the moon is a different color.

What Emerald pastiches isn’t the actual content of a Lovecraft story—no hoary tomes, no detailed descriptions of the inhuman anatomy. Instead, it mirrors the eerie fascination and joy of the Mythos reader. Victoria is an eldritch horror, but her subjects take real comfort in her awe-inspiring presence. Anyone here who seeks out Cthulhu and Shub-Niggurath in safer form, and comes away both comforted and unsettled, can relate.

Anne’s Commentary

I was a perfect victim, er, subject, er, reader for this story since somehow I’d never read it before. From the title, I deduced I’d be dealing with Sherlock Holmes, who made his first appearance in A Study in Scarlet. From the first faux-Victorian ad, I saw that the Cthulhu Mythos would play a part, for “The Great Old Ones Come.” Okay, great! A tasty mash-up of Conan Doyle and Lovecraft!

And so, first read-through, I zipped blithely along, noting that the first-person narrator was unnamed but thinking nothing of it. As for his new roommate, the consulting detective, I didn’t notice he was never named either until about halfway through. Kudos to Mr. Gaiman, for playing so surely on my assumptions: of course the narrator must be Watson and the detective Holmes, even in a parallel universe in which the advent of the Old Ones, not the Norman invasion, is the pivotal event in English (and world) history. Augh, I feel like Watson at his densest. You know, like the sweet but bumbling Nigel Bruce, Basil Rathbone’s sidekick.

Yeah, I was a little uneasy when “Watson” described himself as a soldier and marksman rather than as a surgeon. Momentum swept me on. I paused again when “Holmes” gave vague feelings as his reason for trusting “Watson” on short acquaintance. That didn’t sound very Holmesian. But the kickers didn’t come until late in the story. First “Holmes” deduced that a “Limping Doctor” was Franz’s actual executioner. A doctor? Limping? Second, the “Tall Man” wrote that he’d read “Holmes’s” paper on the Dynamics of an Asteroid. Wait a minute! Holmes didn’t write that, Moriarty did! But this is all messed up, or is it? What about the narrator’s signature, S____ M____?

Don’t assume. Deduce. In a universe where Old Ones rule Earth circa 1886, it makes sense for Moriarty and his chief henchman Sebastian Moran to be the “good guys,” while Holmes and Watson are the seditious criminals. As this version of Moriarty says, it’s all morally relative: “If our positions were reversed, it is what I would do.” Could the Holmes of Conan Doyle’s England, transported to Gaiman’s Albion, serve rulers who demand the price of minds (souls) for their general benevolence? No way. Could Conan Doyle’s Moriarty countenance such a price and thrive under Old One dominion? Sure.

Excellently done, Mr. Gaiman! You turned my mind inside out, and I enjoyed it.

The other great fun of “A Study in Emerald” is trying to figure the Old Ones out. Who’s who? We’re told they return to humanity from R’lyeh and Carcosa and Leng. Some of them, by name and description, are fairly obvious. The Black One of Egypt, who looks human, must be Nyarlathotep. The Ancient Goat, Parent to a Thousand, must be Shub-Niggurath. I’m thinking the Czar Unanswerable is Hastur the Unspeakable. The White Lady of the Antarctic Fastness? Ithaqua would be the one most likely to enjoy that chilly climate, and it could be a “Lady” as well as a “Lord,” right? What to make of the more cryptic rulers, the Queen of Albion and He Who Presides over the New World? Well, since we still need someone from R’lyeh, one of them should be Cthulhu. I vote the huge Queen, even though “she’s” not said to be octopoid. What about the “Presider” (President)? Yog-Sothoth? Tsathoggua? Somebody/Something else?

This is your essay question, students. You have one hour to respond.

The other Mythosian of great interest is the lake creature who attacks Moran. Even more interesting is the implication that (as Lovecraft himself would have it), the Old Ones are not the only political party in the cosmos, nor are they necessarily all perfectly united. The gods of Afghanistan are rebellious, refusing to be ruled by Albion or Berlin or Moscow. Victoria (Cthulhu?) sends troops against them and their human worshippers, with little apparent success. Moran notes apprehensively that trouble brews in Russia, where the Czar (Hastur?) reigns.

Most humans seem to accept Old One rule, as evidenced by applause for the play about their coming. Moreover, they can do good. We’re told they’ve saved mankind from its barbarism. They provide prosperity, prevent war [RE: How can you have battle-scarred veterans if you’ve prevented war? Maybe they just call it something else…]. The Queen heals Moran’s withered shoulder with one touch. Yet they do demand terrible sacrifices (Franz’s little diversions being the example), and rebels like Holmes and Watson can’t accept this. Self-rule, whatever the odds and the price!

One lovely example of Gaiman’s craft before we go. Moran gazes at his healing scar and hopes it’s not just the moonlight that makes it look pink rather than frog-white. Pink? From moonlight? Later we learn from the Old One play that their coming changed our nastily yellow moon to a comforting crimson. Stellar detail. Stellar staying within Moran’s POV, for he’d never explain to us or himself why the moonlight was pink-tinted and pink-tinting. We the readers have to wait for that revelation until it can be elegantly introduced.

That’s how one builds worlds that convince.

Next week, we meet one Lovecraft’s pulp collaborators, A. Merritt, for “The Woman of the Wood.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in April 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.